NYC Omega Black College Tour 2014

This afternoon, YMI Cultural Center was honored to welcome 80+ students and their chaperones on this year’s Black College Tour sponsored by Xi Phi chapter of Omega Psi Phi. This annual tour introduces a group of students from the New York metropolitan area to a selection of historically black colleges and universities. (HBCU)

Since 1988 the Black College Tour has taken hundreds of students from the New York metropolitan area to 16 historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCU) in North Carolina, Virginia, Washington, D.C., Maryland, Delaware and Pennsylvania. The program is enhanced by preparatory workshops designed to give students a greater understanding of their career options and the educational requirements needed to fulfill them. Eighty-five percent of the students who participate in the program go on to college. Thirty-five percent of those students choose a college that was visited on the Tour… (from their website)

After being denied education for so long, upon emancipation freedman embraced every opportunity to learn. Those who could read taught others. Churches housed schools. And around the country, HBCU began to form. After the second Morrill Act of 1890 was passed, states that excluded black students from their land grant colleges were required to establish separate land grant colleges for them.

There are 106 historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) in the United States, including public and private, two-year and four-year institutions, medical schools and community colleges.[2][3] Most are located in the former slave states and territories of the U.S. (Wikipedia)

I was asked to make a presentation to the group about the history of YMI. I was thrilled to be able to share my knowledge of some of the founders and leaders of YMI and Asheville’s black community, and how HBCU influenced the course of their lives.

In YMI’s history, William Trent and Dr. J. W. Walker were both graduates of Livingstone College who were instrumental in YMI’s early days. Dr. Walker received his medical degree from Leonard Medical School of Shaw University. Mr. Trent later became president of Livingstone College. Both Mr. Trent and Dr. Walker’s wives were also graduates of Shaw. Ernest McKissick attended Shaw with the help of Mr. Trent and Dr. Walker. His son Floyd McKissick later attended Morehouse College and enrolled at North Carolina College (NCC) Law School, later North Carolina Central University, but he also successfully sued for admission to UNC Law School and became the first black student to be admitted there.

Many graduates of all-black Stephens-Lee High School went on to attend HBCU, including Dr. Frank O. Richards, a Stephens-Lee High School graduate who received his medical degree from Howard University. About a dozen students from Stephens-Lee High formed the Asheville Student Congress on Racial Equality (A-SCORE). Mr. Marvin Chambers, A-SCORE founding member and community leader, pursued his engineering degree from North Carolina A&T, and said he wouldn’t trade the experience and education he received there for a million dollars. Attorney James E. Fergusen, II, another A-SCORE founding member, later went on to become student body president at North Carolina Central University. Many of Asheville’s current leaders include graduates from HBCU.

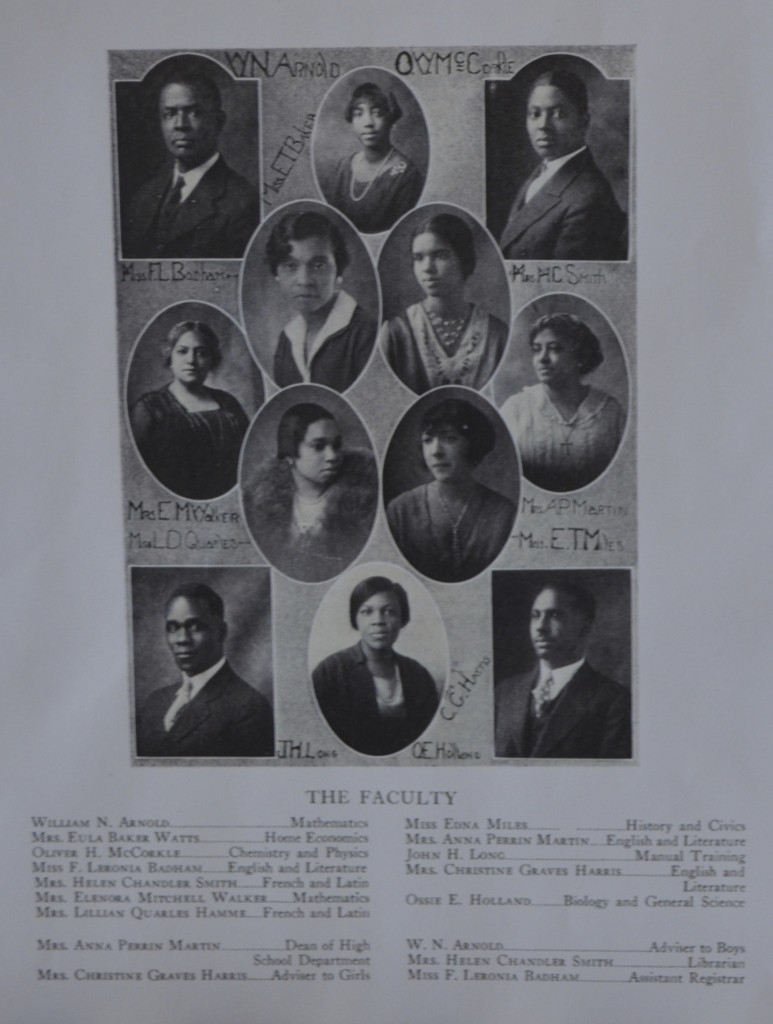

My own family history includes several members who attended HBCU including the siblings of my great great great grandmother, Mary Jane Jamison Mason. Her sister, Sally Jamison Malone, attended Walden University, a historically black college in Nasheville, TN before moving to Topeka, KS where she ran a Florence Crittenden Home for Unwed Mothers. Their brother, Dr. James Monroe Jamison, was part of the first graduating class from Meharry Medical College, the first medical school in the South for African Americans. My great great grandfather Reginald W. Stewart attended Lincoln University. My great grandmother Addie Jane Johnson Stewart graduated from Morgan College (now Morgan State University) in 1917. She later taught one of her neighbors to read. I am sure that in many cases, people came home from HBCU and their education and leadership experiences caused a ripple of positive change around them as they served as role models, educators, and professionals in their communities.

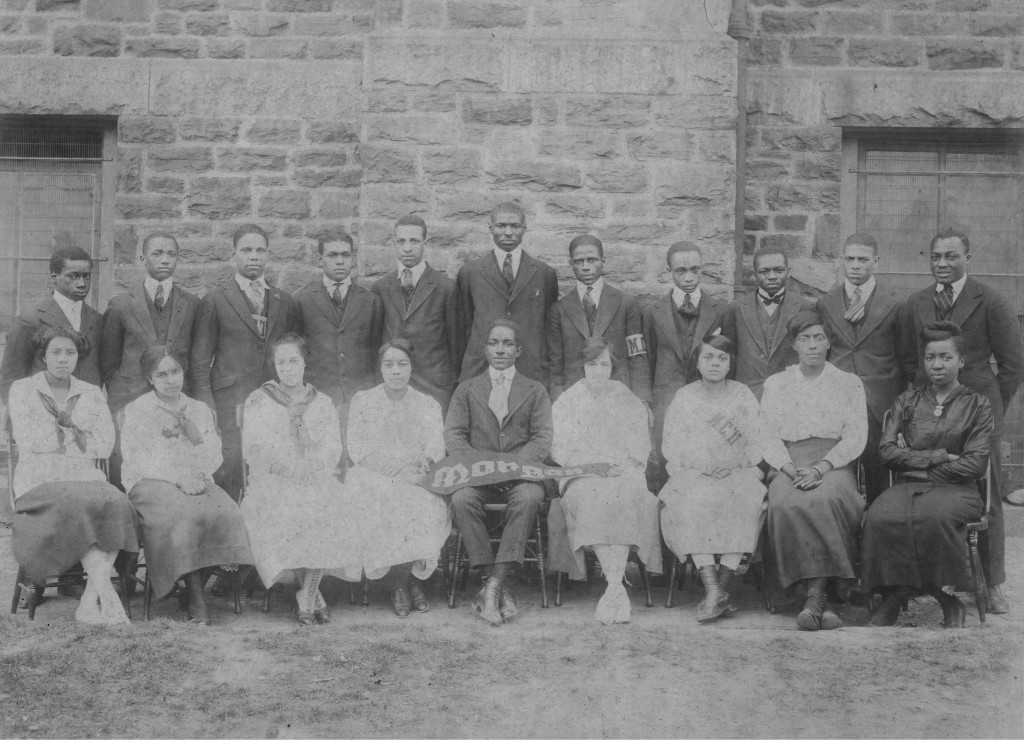

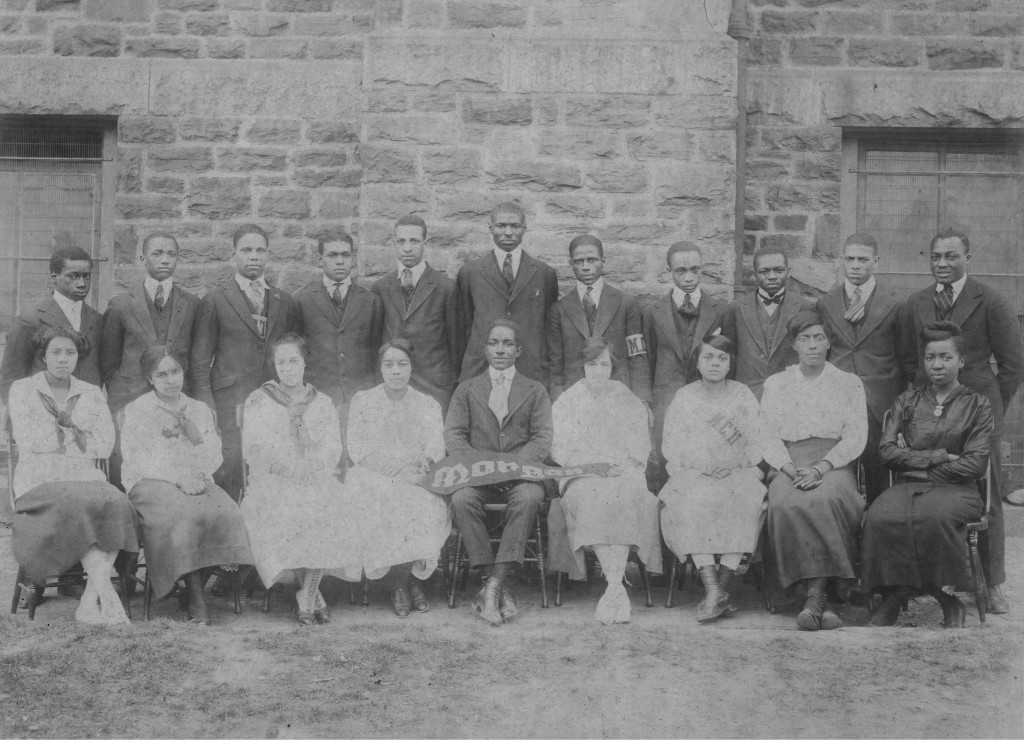

Morgan College, 1917

(Addie Jane Johnson, front, 2nd from left)

I had something particularly special to share with this group of visiting students and Omega Psi Phi fraternity members. In one of our old family photo albums, my great grandfather Samuel Stewart had included photos of his friend Nathaniel Burrell, with whom he served in the US Army during World War I. In researching Mr. Burrell’s life (wondering if he might have been some relation), I learned that Nathaniel Burrell went on to become a charter member of Omega Psi Phi’s Xi Phi Chapter in New York City.

Nathaniel A. Burrell, Jr.

US Army, World War I

In researching HBCU in preparation for the students’ visit, I found an article from the LA times that said black students attending a four year HBCU have a 70% graduation rate, versus 30% for black students at predominantly white colleges. Some other benefits include being surrounded by black achievers and leaders, no longer being a minority in the school community, smaller class sizes, diverse curriculum, caring staff, role models, continuing the legacy of HBCU, lack of discrimination. Of course, many HBCU struggle with funding and with keeping costs down, so students have to weigh their needs against what each school has to offer. Choosing a college is a very personal choice influenced by many factors, but I hope that the students come through this journey feeling inspired and encouraged to continue the legacy of HBCU.

The White House just released its first class of HBCU All Stars: 75 undergraduate, graduate and professional students for their accomplishments in academics, leadership and civic engagement. Hopefully these colleges will remain strong and healthy, fostering the growth of the next generation of leaders. Wherever their paths lead, I asked the students visiting us today to remain life-long learners: to read, to find their own gifts, and then find ways to give back to their communities.